I. Introduction

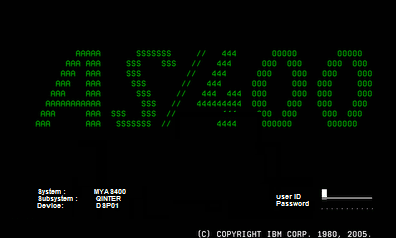

“Nobody Can Hack an AS/400.” “Never in my 40 years in the business has anyone hacked an AS/400!” “AS/400’s don’t have hacking problems like Windows computers.” “AS/400’s are bullet-proof. They don’t have zero-days like other computers.”

If you know anyone who works with an IBM i (formerly known as "AS/400", also branded as "eServer iSeries"), you may have heard some of these statements, typically spoken with the emphasis of someone who wants it to be true; someone willing to speak loudly enough to overcome their sense of dread: that they may be wrong.

… and you may be surprised at just who is using IBM i in 2020.

We (Security Researchers Matthew Carpenter and Roni Michaels) decided to dig into these beasts of old to answer a few question:

- Is the IBM i "old" and inherently vulnerable?

- Or Is it a hardened ecosystem whose design and age shield it from hackers?

- Are it's notable uptime percentages an indicator of a safe environment?

- If the IBM i machines *can* be secured, how are common practices doing to maintain secure systems?

- How hard is it to hack an IBM i?

- Where is the security "crunchy outer shell" and how do we get to the "soft gooey middle"?

- Given their presence in critical infrastructure, how do we best protect them?

This blog series will share the history and context of IBM i systems, some technical grit, and security recommendations. While our research has only begun, along the way you should gain some key insights into how to think about and approach security for your AS/400’s. If you are a security researcher, you may learn that you have a new passion for big-iron.

First, a bit of history...

II. The History

In the beginning... scratch that. In 1988, I.B.M. (you know, the one illustrated in the movie "Hidden Figures") released a brand new minicomputer called the Application System/400 (AS/400). It was the successor to the illustrious System/38, first released in 1979 with the first-ever 48-bit address scheme, allowing 281,474,976,710,656 unique addresses (or numbers) to be worked with, and great effort was made to carry the legacy of System/38 programs over to the AS/400. In the 1970's the term "minicomputer" was coined to describe computer systems which could be purchased for under $25,000 (current value: $165,000).II. The History

In 1988, the AS/400 (consequently running Operating System/400, or OS/400) was sold to small to mid-sized businesses around the world, providing all the servers one could want in a time before the Internet's tectonic plates were solidified and cooled. The machine would run database, application, web, file and mail-server, and was designed to operate at full capacity (ie. the CPU pegged all the time). Over the years, the IBM AS/400, later the iSeries and still later IBM i, became synonymous with reliability and dependability. Many smart individuals have made their careers attaching themselves to this pervasive platform.

The AS/400, like all computer system families, underwent considerable improvements over the years, with upgraded processors, features, software packages, and of course, names.

Most notably, in 1994 IBM introduced the AS/400 Advanced 36, a replacement for the System/36 system, sporting a brand new 64-bit PowerPC-based architecture to replace the aging and proprietary 48-bit architecture. IBM had already been using PowerPC in their RS64 family of processors running AIX. As part of the A.I.M. Alliance (made up of Apple, IBM, Motorola) who started PowerPC architecture as the next step beyond Intel's aging "x86" processor family, IBM contributed the majority of the PowerPC Instruction Set Architecture from its existing systems, and continues to be the largest high-end user/implementer of PowerPC. Perhaps that's why they let OS/2 die the sad death it did... but I digress.

In 2000, likely to keep fresh and new in the Internet "e-Commerce" and "e-Business" era, IBM rebranded it's servers under one "eServer" family, renaming the different platforms zSeries (Mainframes), iSeries (AS/400), pSeries (POWER), xSeries (Intel-based servers). OS/400, the AS/400 operating system was also renamed i5/OS, paralleling the POWER5 chip at its core. At the time, many of us didn't understand the irony of keeping the iSeries and pSeries separate. While pSeries AIX systems made sense, the p in pSeries indicated the POWER architecture, which iSeries was very close to in all but name. While in 2006 iSeries was rebranded again to "IBM System i," in 2008 IBM officially combined the "p" and "i" architectures into one "Power Systems" line.

All this history should hint at a few things:

- IBM i has a long and rich history through several eras of computing and connectivity, with vigilant supporters and defenders of the architecture

- IBM i has certainly risen to new challenges to keep up with today’s modern processing power needs

- IBM i is *not* the arcane 48-bit system it started out to be, but a very powerful and well designed PowerPC architecture

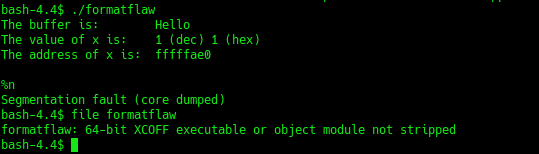

- And as PowerPC, many of the hacking tool-chains and some exploit components work just as well on IBM i as on other architectures.

Interlude…

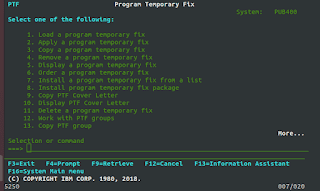

Before we move into a discussion on hacking and security, we’d like to bring up an important topic that is worth jumping the gun on, and that is the topic of backups and patching. In preparation for this blog series, we conducted a number of interviews with owners/operators of IBM i systems, and were baffled at the number of systems which are not patched regularly, or that don’t have backups or disaster

recovery plans. It seems these systems have become so critical to operations that they “cannot afford to be down.” This concerns us at a very deep level. Patching and backing up your systems are a protection from what is to come. Backups are vital for recovering from cyberattacks, as once a system has been compromised an admin cannot trust that they have removed an attacker's presence completely. Patching is required to support the stability and security to prevent “bad guys” or bugs from taking down your organization.

The best responses we received were that some customers had deployed IBM i systems in failover pairs. Periodically they would apply patches to the offline system, then “fail over” to using that one, allowing up-to-date software patches to be running for a time. Unfortunately, that happened every X months.

Pro tip: If your system is too critical to be offline for patching and backups, you’re doing it wrong. These systems want to be maintained, and while having a high uptime is emotionally gratifying and supportive of your IBM expenditures, scheduled downtime (aka a “maintenance window”) for such vital things as backups and patching is important for your longevity. If you have avoided the repercussions of not having patched or backed up, we are thankful for your good fortune… but it is simply good luck.

Now back to our regular programming.

III. What is Hacking?

There are many definitions of hacking, some benign and some malicious, and many in between. For our purposes, let's choose the following definition of hacking: To repurpose or coerce a computer system using weaknesses and vulnerabilities to gain unintended access and cause it to behave in a way it was not designed nor intended. In other words, study a computer system, consider the value to an attacker if compromised (activities or information), identify and analyze attack surface, and leverage both technology and people to obtain the desired goals.

Also interesting, the survey indicates that as many as 18% of installations in 2020 are running IBM i version 7.1 or below, which have been unsupported by IBM since 2018… but more on that and other interesting things in future posts.

So once again, "Everybody" is using IBM i. Our key interest was sparked by the transportation industries, but this research will hopefully benefit all areas of IBM i alike.

IV. Who Uses IBM i?

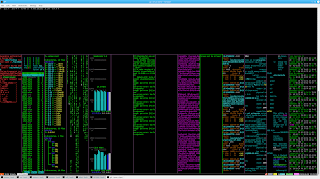

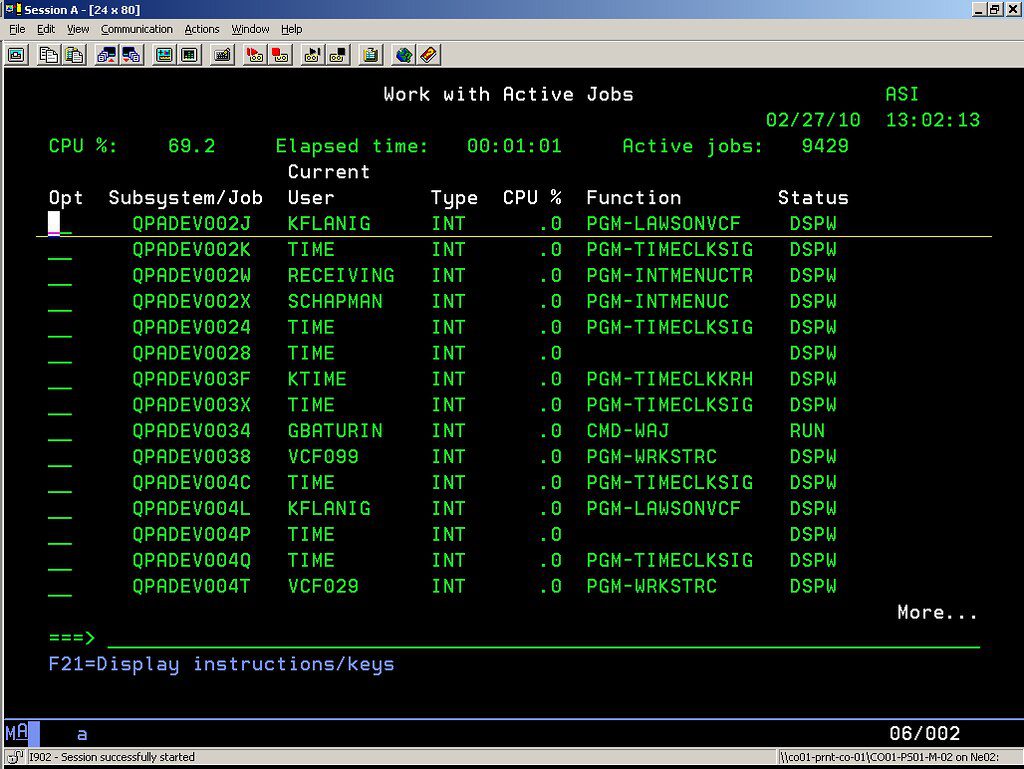

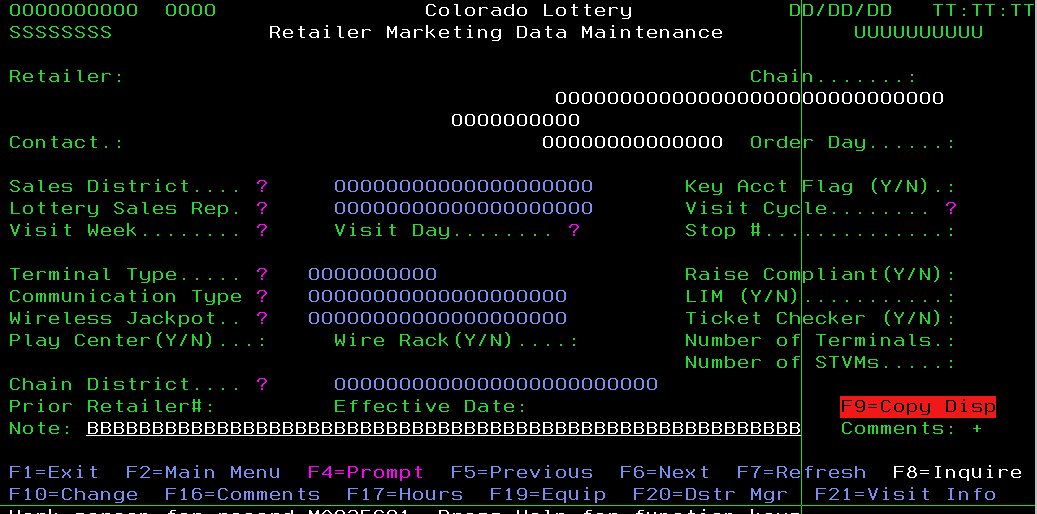

Everybody! While some customers may have migrated to other platforms over the years, in our research we've discovered no great diaspora, no large migration from AS/400 to Intel systems, although many options do exist for that exact thing. IBM i people tend to bleed blue, and generally for good reason. IBM i at its core is a powerful database engine strapped to a scalable and almost affordable piece of hardware that has plenty of extra resources for running all the Internet services you could want. IBM has even provided a nice "Navigator i" software package to help manage the servers without even touching a green-screen (I laugh as I write this blog post in VI in timeless green on black terminal). More on "Navigator i," which is based on CIFS (aka Samba) file sharing. Back to the question at hand...

According to a 2020 Market Survey for IBM i performed by "HelpSystems" (whose business model benefits from accuracy, not manipulation of this data), IBM i is widely used in numerous vertical markets, including Manufacturing industry as the biggest customer, with Banking/Finance close behind, then IT Software Development followed by Transportation/Logistics/Distribution, with still considerable usage in Retail, Insurance, Tech, with some usage in HealthCare, Government, and Utilities.

V. Mapping Hacking to IBM i

What does hacking an IBM i look like?

Well, let's recount how we approach hacking:

- Study a Computer System

- Consider the Values Hacking the System Provides

- Identify and Analyze Attack Surface

- Leverage Technology and People to "win"

As we started writing this blog post, we were both awed by the number of topics we wanted to discuss. In good time, my dear Watson.

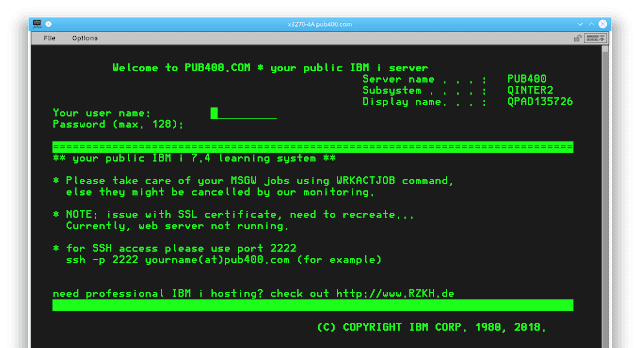

To begin, let's just say that we're still studying. We've spent time with industry experts at multiple levels, and spent hands-on time and learning time with multiple systems (if you're interested in getting familiar with IBM i, check out pub400.com, one free resource on the web for just that!).

Let's consider the values that we can gain by hacking an IBM i. What can we do if we control user accounts or systems which we should not have access to? For simplicity, we'll just touch a few... but allow your own mind to play a little here for a clearer picture:

- Manufacturing: Controlling Mix Elements and Processes to make things go BOOM

- Banking/Finance: Manipulate wealth and debt for all of an organization's customers or holdings

- Transportation: Dramatically reduce efficiency of shipping and trucking. Potentially, with Telematics, controlling the vehicles themselves

- IT Software Dev: Insert Backdoors and Vulnerabilities into code before shipping

- Government: you get the picture

Let's re-emphasize that hacking a computer system comes in two primary forms: Information and Access (which sometimes leads to cyber-physical impact, like spitting money into the street at an ATM or driving a truck into a government building or a church). Sometimes the best things a hacked computer system gives is access to others... although with IBM i, it's safe to assume that much of the data and access we're interested in sits right there in that box... or some other IBM i systems nearby.

Next step, identify and analyze the attack surfaces of the IBM i. This is a long part of the blog post series, and will come with identification of concerns as well as recommendations.

However, as a teaser we'll just set this down over here....

- TN5250/3270/Telnet unencrypted access

- Navigator i

- SAN disks

- HTTP Server

- RPG and COBOL and CL programs

- Mail Server

- FTP and S/FTP Servers

- DB2

- ERP systems like SAP, JDE, etc...

- PASE (basically AIX on IBM i)

- Custom C/C++/Python/Java applications

- Custom RPG/COBOL/CL applications

- EDI

- NTP

- others...

There are a great deal of things to play with, and we're looking forward to digging into this with you in the coming months.

VI. Interim Conclusions

So, we've opened many cans of worms. Conclusion is probably the worst term to use. However, in summary, IBM i is very much alive and well, and from a power and functionality standpoint, a very attractive solution for critical and high availability applications. How does it stand up to security? Can it *be* secured? Assuming it *can* be, how are we doing? And finally, what can you as IBM i users do to better protect your enterprises and governments from hostile take-over of these mission critical work-horses?

Some future episodes will include:

- Users and Passwords

- Languages and Hacking

- Exploitation and Securing IBM i

- Architecture/Obscurity

- Remote API attacks

- Culture

- Running code as other users

- Common Apps + Security

- Survey of Common Practices

- Insecure Access Methods

- System Discovery by Internet Search Engines

- Attack Surfaces, Exploits and Mitigations

Stay tuned!

Matt and Roni

--

We would like to thank NMFTA for their support and collaboration in this blog series.